By Rachael Maciasz, MD

I wasn’t really sure what I was getting into when I decided to be a doctor. My impression of medical students was that they were driven people who love to learn and want a satisfying and rewarding career. Sounded like me!

Everything was going great until I got to my third year of medical school and I started doing what I had worked so hard to do—see patients.

I had long conversations with my boyfriend, who loved hearing my interesting stories from the wards. “I just felt like today we missed something.” He was confused, even bewildered. “Wait! Isn’t this what you have been working so hard for . . . to see patients?”

“I feel like we are not being honest with the patients! They are so sick, but we don’t address the reason why they are sick. No one says, ‘You’re overweight, that’s why your knees hurt.’ Or, ‘You’re depressed. That’s contributing to your chronic pain and anxiety.’ We treat the issues with pain drugs or antidepressants. We don’t invest much time in explaining the situation to our patients.”

I felt that being a doctor meant just putting a Band-Aid on hemorrhaging wounds, ones that could likely be the end for these patients.

As I continued with my training, my feelings of disbelief and dissatisfaction persisted. During my time as a medical student, I watched the same story repeat itself over and over. The resident and the attending doctors examined patients, spent a short amount of time explaining extremely complicated medical decisions, and then ran out the door to the next patient. The hospitals were dark and sterile, the rooms depressing and little light shone through the windows. Not a sign of healthy life existed in these places. Not even the doctors looked well. I had a deep, burning feeling that we were missing something.

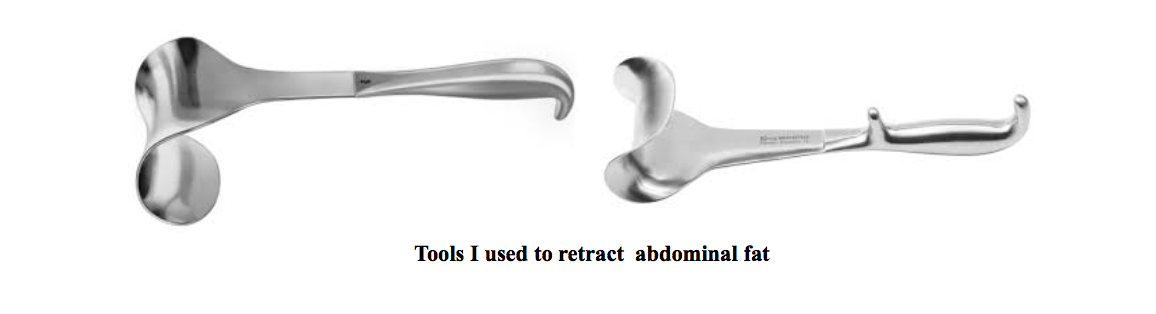

During my surgery rotation, I participated in an exploratory laparotomy. This type of surgery is done when doctors are unsure of why a patient has very concerning symptoms and need to look inside the abdomen for possibly lifesaving intervention. In this case, the patient had severe abdominal pain and persistent fevers. I took my usual stance in the operating room and assumed my job – to hold back the abdominal fat while the surgeons did the technical work.

This time my job was more challenging than usual. The patient was over 600 pounds. Her body filled the operating table and then overflowed off the sides. Holding the fat back took multiple medical students and a lot of physical labor. I was shocked the surgeons were operating on her at all knowing that, at this unhealthy weight, her chances of surviving a surgery were slim. But, I also knew that the risk of not having the surgery was likely death.

The surgeons found the problem and quickly took care of it. They removed a piece of bowel that had lost blood supply, was now dead, and had been rotting in her abdomen.

I got to know the patient while she was in the hospital recovering after her operation. The operation had truly been lifesaving. In fact, this was the second lifesaving surgery she had had. Yes – she had once before had a dead piece of bowel that had been removed. I learned she had weighed 600 pounds for many years. She had lost the ability to walk. She needed machines to move her in bed so she did not get bedsores. She never left her house. Yet she was eternally grateful for what the surgeons had done for her – twice now.

I spoke with the surgeons about what I perceived as the real problem: this woman weighed 600 pounds. The surgeons completely agreed. The reason why she had rotten bowel inside her was because she was so overweight. I asked if they would operate again. The answer? Likely no. I asked if they felt she was getting adequate care from our health care system. Surely, the patient was well cared for in the hospital, both before and after the operation. I was trying to understand the seed that was growing inside of me – an idea that adequate care would have been helping her do anything and everything she could to prevent this from happening, not just fix it after the damage was done.

The surgeons’ answer was that it wasn’t their job. And they were right. They had done their job. They had saved a life. I felt pain in my heart knowing what was next.

This woman would likely return to her previous state of living alone, unable to move, until her next episode which she might or might not survive.

I began to wonder, if I were her primary care doctor, what sorts of things would I want to offer her? What about ensuring her a place in a medical weight loss program? What about helping her gain control of her life so she could one day walk again? Encouraging her to get into counseling to explore what made her eat to gain so much weight? Would it be possible for the trajectory of this patient’s life to change? I wanted to find answers to these questions.

So I began to search. I spent hours scouring my email, medical school list serves, and the internet for opportunities to learn about people who thought more like me, who asked questions like, “What is adequate care?” “How can we help people have tools to live more healthful lives so that they can regain control?” “Can I find anybody who thinks that this woman needs more than a surgery?” I thought that she needed a team to help her remake her lifestyle!

Enter LEAPS into IM– Leadership and Education Program for Students in Integrative Medicine. The program, sponsored by the American Medical Student Association, jumped off the webpage at me. I immediately applied and was soon accepted to join the weeklong retreat with other medical students from around the country to learn about integrative medicine and self-care.

At LEAPS I met medical students like Jack Temple, who is now my colleague in International Integrators and is fascinated by nutrition and integration of healing techniques to complement biomedicine. And like Kristina King, a medical student with the amazing experience of having studied naturopathic medicine before allopathic medicine. I met Annie Robinson who is passionate about storytelling as a therapeutic means and launched a stories forum for medical students. I met practicing doctors, including Kathryn Hayward and Bill Manahan, who had spent time in their careers investigating other avenues to health and healing which they openly and excitedly shared with me.

These people, and many more, became my mentors and my friends. They have taught me that there is so much more to healthcare than being sick in the hospital. Integrative Health looks at the whole person, not just the diseases they present with, and complements biomedicine by helping them incorporate healthy mind and body techniques as adjuncts to their healthcare. I met many who have worked through their own illnesses and have helped patients work through theirs by incorporating conventional medicine with Integrative Health techniques including nutrition, movement, exercise and mind/body/spirit practices.

I do not know if it was possible to change the trajectory of the surgery patient’s 600-pound life. In doctoring, we like to call our patients our teachers. What I learned from being witness to her experience was that if someone (her internist? a therapist? a nutritionist? me the medical student?) had explored her potential, perhaps the patient could have changed her life. Maybe she would like meditation. Maybe she would like a physical therapist to work with her doing gentle range of motion until she could move more freely. Maybe we could have identified a person to cook healthful meals for her and give her support in changing her eating habits. Perhaps daily psychotherapy to explore her past traumas combined with touch therapy like gentle massage or jin shin jyutsu would allow her to feel cared for and nourished and start a change. Surgery was a necessary Band-Aid, but Integrative Health –exploring her whole self—might have laid the foundation for a new life.

As a resident physician I still leave work feeling disappointed. The patients are really sick and the hospital health care system is still a dark place and focuses on quick fixes and not on foundations. I truly believe people are trying to do their best and I understand that sometimes a system is difficult to change. If I had my way, the walls would be full of flowers and plants, sunlight would stream into every room, and patients would be fed gourmet organic meals full of vegetables and fruits. Health care would focus on self-care. How can patients leave this hospital and have the tools never to come back?

I can feel there is change on the horizon. Through working with people in International Integrators, I am filled with hope and gratitude. I know the hospital is a place where desperate measures save lives, but that there is more to health care. There are practitioners that focus on healthy self-care – teaching patients Integrative Health techniques to care for themselves. We have a long way to go, but working with inspiring people like Kathryn, Bill, Annie, Kristy and Jack – all colleagues organizing the Living Whole retreat, I can see that, as a doctor, I am able offer my patients care with the whole person in mind. Care that doesn’t address one horrendous problem but that addresses their personal situation and their courage and willingness to change. I don’t have to just place Band-Aids.

Rachael was born in Michigan and always appreciated the connection among food, health and the mind-body connection. She studied Cultural Anthropology as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan where she made all her friends go to the farmers market with her. She pursued her interests when she moved to New York City and worked for Healthcorps, mentoring high school students in health and wellness. Her curiosity about people’s health narratives inspired her to attend medical school. She completed clinical research in palliative care at the University of Pittsburgh and then graduated medical school from SUNY Downstate. She is currently a resident in training in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at Tulane University and wants to pursue a career in integrative palliative care.