By Barbara Braver

I am sitting in my comfortable chair with a mug of tea, sorting myself out and moving into my new day. My morning ritual is in a quiet corner of our old house, which has stood on this rocky New England coast for more than three centuries. I am recent to it, having been part of its life for only the last half century.

I view the morning through the two front windows of this room, which are “6 over 9” meaning there are six little panes of glass on the top half of the window – two rows of three each – and nine on the bottom half in three rows of three each. Each pane gives me a different picture. My neighbor’s son’s battered old red truck is in the center of one little pane, and our crab apple tree, its bare branches raised, shows up in another. Clouds float through one while in another, just feet away, the sky is clear and pale blue.

I view the morning through the two front windows of this room, which are “6 over 9” meaning there are six little panes of glass on the top half of the window – two rows of three each – and nine on the bottom half in three rows of three each. Each pane gives me a different picture. My neighbor’s son’s battered old red truck is in the center of one little pane, and our crab apple tree, its bare branches raised, shows up in another. Clouds float through one while in another, just feet away, the sky is clear and pale blue.

Perhaps there is something in here about perspective: point of view, my filters and lenses and how I choose to look at things. As I have become ever more acquainted with myself over the years, the better I understand how fully I can be controlled by my filter, that is by my lens – whichever one I happen to be wearing. For example, this past Monday – a new week and a new start in mind – I weighed myself, something I hadn’t done for weeks and had been putting off by getting dressed before I “remembered.”

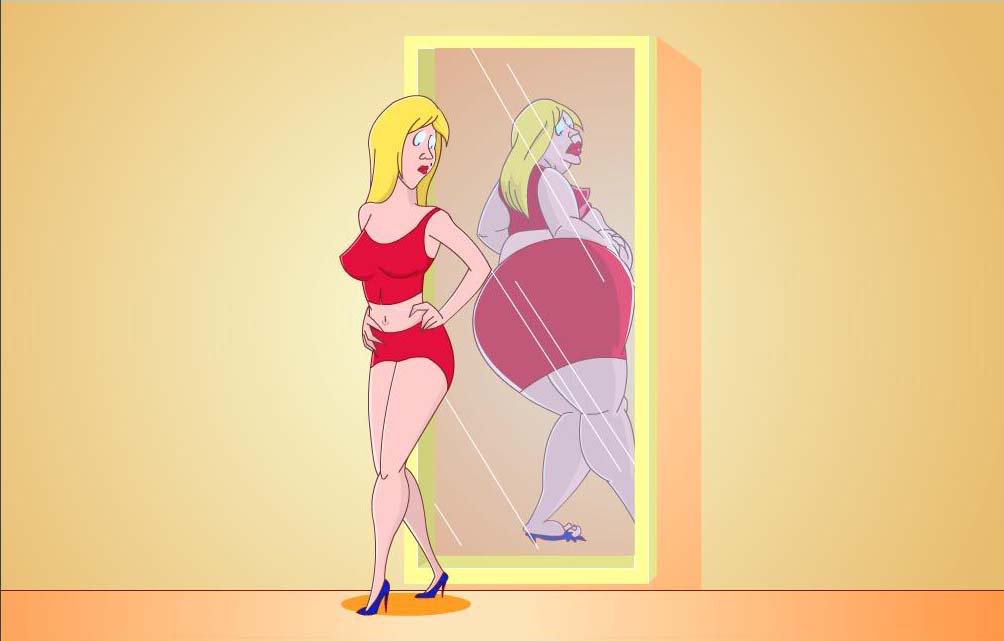

So, Monday morning: I creep nude onto the digital bathroom judge, touching down ever so gently, and stare down at gigantic numbers. Whoa! These numbers are a bad surprise, and because of them, I begin to view the world through my fat lens. With my fat lens on, I am prone to judge everyone who crosses my path as if I were the buyer at a cattle auction. Worse, I judge myself as if my life’s purpose is to be at whatever I might imagine as the perfect weight.

So, Monday morning: I creep nude onto the digital bathroom judge, touching down ever so gently, and stare down at gigantic numbers. Whoa! These numbers are a bad surprise, and because of them, I begin to view the world through my fat lens. With my fat lens on, I am prone to judge everyone who crosses my path as if I were the buyer at a cattle auction. Worse, I judge myself as if my life’s purpose is to be at whatever I might imagine as the perfect weight.

My fat lens is firmly on as I waddle to the closet wondering if anything in there will fit me today. I just washed the black jeans hanging near the front and after turning around in the hot dryer air they always shrink at least several inches in the waist and need to be tugged to close around the enormity of what is known as my waist. Sweatpants, that’s it, because I plan to sweat a lot today. I plan to sweat off several pounds before the day is over. I put on the black sweatpants and a shirt with – of course – vertical stripes because everyone knows vertical stripes make you look thinner.

My fat lens is in full control as I make my way out the door without breakfast. Who is that emaciated woman trotting down the street with her ponytail swinging? She looks like a tall toothpick. And there is Betty, the neighbor I often spy walking into her house with pizza boxes. She is hoisting her girth behind the wheel of her old Ford. She is definitely a candidate for vertical stripes, but I don’t think she really cares, or she wouldn’t eat all that pizza.

So far, this day is not going well. A wiser inner awareness finally kicks in and awakens me to the distortions of my fat lens. I rip it off and return to myself. I wave at Betty and she shouts me a Good Morning and backs out of her driveway.

Evagrius Ponticus, the 4th century desert monastic and theologian, had wisdom on the topic and named such ways of coming at the world. His insights provided the root for what we call the seven deadly sins: pride, covetousness, lust, anger, gluttony, envy and sloth. The seven deadly sins label has a certain fascination and has been an inspiration to artists over the centuries.

Evagrius Ponticus, the 4th century desert monastic and theologian, had wisdom on the topic and named such ways of coming at the world. His insights provided the root for what we call the seven deadly sins: pride, covetousness, lust, anger, gluttony, envy and sloth. The seven deadly sins label has a certain fascination and has been an inspiration to artists over the centuries.

However, as Evagrius explained, these lenses aren’t so much sins in themselves, but rather ordinary emotions or ways of being that can quickly lead you astray if they run amuck and dominate your consciousness.

It is perfectly fine to be proud of your kids, to want things – including the delights of physical intimacy and, let’s say, the double fudge brownie or perfect martini. It is certainly normal to be angry at evil deeds or to think the grass is surely greener elsewhere, or that someone else has better hair, or to mope about on the couch from time to time watching the shopping channel. It is the excess part that can do you in. When your worldview is overly influenced by any of these quite ordinary ways of being a living person, the trouble starts. Looking at the world through one of these lenses, particularly when you have no idea you are wearing it, can thus dispose you to sin, or – less tidily put, can make you really mess up. Evagrius knew that back in the 4th century and I learn it again, and yet again.

It is perfectly fine to be proud of your kids, to want things – including the delights of physical intimacy and, let’s say, the double fudge brownie or perfect martini. It is certainly normal to be angry at evil deeds or to think the grass is surely greener elsewhere, or that someone else has better hair, or to mope about on the couch from time to time watching the shopping channel. It is the excess part that can do you in. When your worldview is overly influenced by any of these quite ordinary ways of being a living person, the trouble starts. Looking at the world through one of these lenses, particularly when you have no idea you are wearing it, can thus dispose you to sin, or – less tidily put, can make you really mess up. Evagrius knew that back in the 4th century and I learn it again, and yet again.

I have other filters that shape my perspective, and my fat lens is not as harmful as some of the other filters I have at my disposal. I have come to know, sometimes at great cost, that the measure of a filter’s harm is what particular aspect of my life it distorts/enlarges/constricts such that I am not able to see what is before me with the naked eye of purposeful inquiry and calm discernment.

Anger is one of the worst, particularly anger rooted in fear, and with incredible sadness we know from the daily news what horror can come out of viewing the world through that lens. My anger lens doesn’t get much use, perhaps because I am more likely wearing my lens of vulnerability.

The word “vulnerable” means being able to be wounded

And aren’t we all. The vulnerability lens is likely to come out of the drawer with

the arrival of unsettling news. Earlier this month, within days, a dear friend was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer, another friend lost his job, another was hospitalized with a still undetermined heart problem.

My vulnerability lens was at the ready. With it on, my frightened eyes see this world as a scary place where we are all hanging by a thread. I am unable to see that – yes – though we are able to be wounded, we are also able to be healed. I don’t see the reality of the actual making of us, the growing of us, the becoming of us through all what we undergo. I forget that, though change is the only constant we can, and indeed do, move through.

In my quiet corner, sipping my tea, I am grateful for a moment now and then of awareness: of my lenses, of knowing that the old phrase “seeing is believing” doesn’t quite describe the complexity of our human reality. As well, I am grateful for a sense of the love at the center of the Universe which holds me in all of my contradictions, my awareness, and – mostly, my unawareness. Ah yes.

Barbara Braver grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where at age 12 she started a one-page weekly newspaper called Neighborhood News. It lasted for a full summer, to the amusement of several indulgent neighbors. This was the beginning of the writing life. After college graduation she moved to the Boston area, drawn by romantic notions of Emerson, Thoreau and Louisa May Alcott. Though this might have been an insubstantial motive, she has never been disappointed. For most of her professional life, she worked for the Episcopal Church, including 18 years serving as the communication assistant for the Episcopal Church’s leader. Since retirement she continues writing, editing and leading retreats.

Barbara Braver grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where at age 12 she started a one-page weekly newspaper called Neighborhood News. It lasted for a full summer, to the amusement of several indulgent neighbors. This was the beginning of the writing life. After college graduation she moved to the Boston area, drawn by romantic notions of Emerson, Thoreau and Louisa May Alcott. Though this might have been an insubstantial motive, she has never been disappointed. For most of her professional life, she worked for the Episcopal Church, including 18 years serving as the communication assistant for the Episcopal Church’s leader. Since retirement she continues writing, editing and leading retreats.